Introduction

More than a century ago, then-Representative William McKinley pursued an aggressive tariff strategy that sought to protect American industry and reduce reliance on foreign imports…The logic was simple: If foreign goods were more expensive, Americans would buy domestic products, fueling economic expansion but the results were not so simple.

What follows is a slightly edited and abridged article from usfunds.com which is entitled “Investor Alert: President McKinley’s Tariff Mishap Could Be a Warning Sign for Trump’s Trade War”.

The Results

Instead of strengthening America’s trade position, the tariff triggered retaliation from other nations. Prices rose, particularly for middle- and lower-income Americans, and political backlash followed. In the 1890 midterm elections, voters revolted: McKinley lost his seat, and Democrats took control of the House.

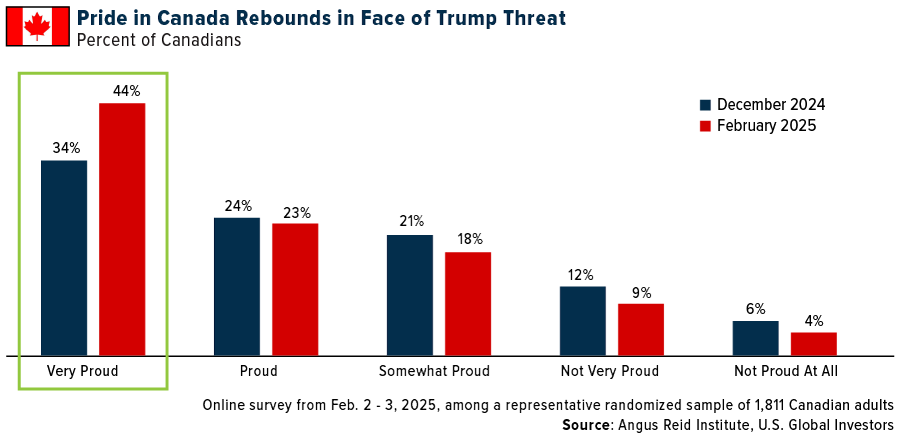

At the time, some Republicans dreamed of annexing Canada, believing that the economic pressure would push Canadians to seek statehood. Instead, the tariff had the opposite effect—Canadian nationalists rallied against what they saw as economic coercion. The country deepened its ties with the British Empire, reinforcing the very trade barriers the U.S. sought to disrupt.

The Reality Today

Fast-forward to today, and we’re seeing some eerily similar trends, starting with an increase in Canadian pride. Due to some of President Donald Trump’s antagonistic rhetoric, we saw Canadians boo the U.S. national anthem during the 4 Nations Face-Off hockey game last week, and a recent poll shows that Canadian pride has jumped 10 points since December 2024.

Trump has made tariffs a cornerstone of his economic strategy, arguing they will bring jobs back to America and reduce the trade deficit but, just like in McKinley’s time, history suggests tariffs don’t actually reduce trade deficits—they often increase them. Why? Because tariffs discourage trade on both sides, leading to fewer exports and fewer imports.

The data backs this up. According to the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE), countries with higher tariffs tend to have larger trade deficits, not smaller ones. And while tariffs may benefit specific industries in the short term, they also raise costs for American consumers and businesses, leading to lower consumer spending and weaker confidence in the economy.

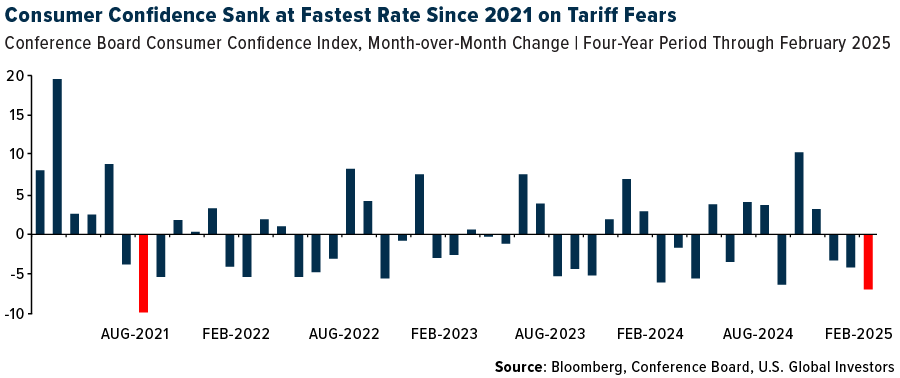

That’s exactly what we’re seeing today. Consumer confidence has been falling, with the Conference Board’s index dropping seven points in February, the largest decline since August 2021.

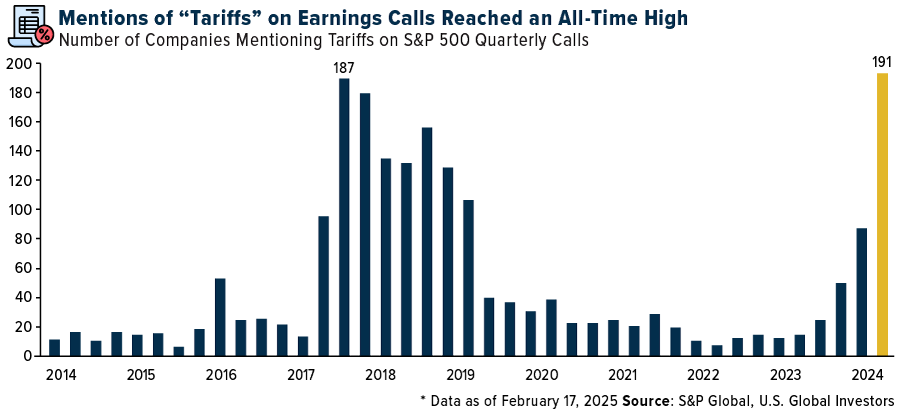

Investors are paying attention: During recent earnings calls, S&P 500 companies mentioned “tariffs” a record 191 times, more than in 2018 or 2019, when Trump first imposed duties on Chinese goods.

How Investors Should Think About Tariffs

1. Tariffs Are a Tax—And Taxes Raise Costs

It doesn’t matter who pays the tariff initially—whether it’s foreign exporters or U.S. importers—the additional cost eventually hits Americans’ pocketbooks. History shows that tariffs lead to higher prices for goods, which can hurt economic growth over time.

2. Trade Volatility Hurts Business Confidence

When tariffs are used unpredictably, companies hesitate to make long-term investments. This uncertainty can slow hiring, delay capital spending and force businesses to look for alternatives—whether that means shifting supply chains out of China or investing in automation rather than workers.

3. Global Trade Relationships Matter

Canada is the United States’ largest trading partner, accounting for $413 billion in imports and $349 billion in exports in 2024. The U.S. also relies heavily on Canadian energy imports, including crude oil, natural gas and electricity.

The unintended consequence of aggressive trade policies could be that Canada—and other key partners—look elsewhere, just as they did after the McKinley Tariff…

Conclusion

History has shown that tariffs often come with unintended consequences, and we’re seeing echoes of the McKinley era today.

Markets thrive on certainty, and tariffs introduce uncertainty. While they may benefit select industries in the short run, they often result in higher consumer costs and slower economic growth. If McKinley were alive today, he might remind us that by 1901—just a day before his assassination—he had abandoned his hardline tariff stance in favor of reciprocal trade agreements. That shift, too, is a lesson in economic pragmatism.

History doesn’t repeat, but it often rhymes—and smart investors know when to listen.